Setting the Scene Link to heading

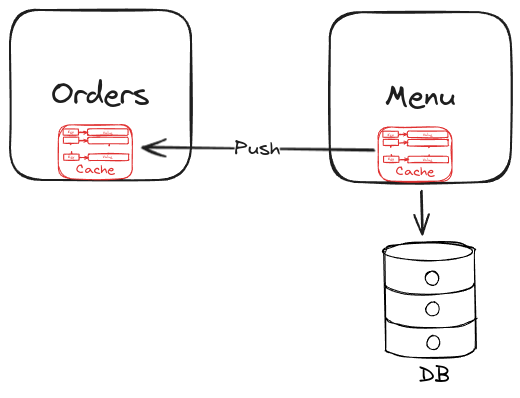

Consider an online food delivery system with two essential microservices:

- Menu Service: Manages the list of available dishes.

- Order Service: Allows customers to create and manage their orders.

How It Works Link to heading

Starting the Menu Service:

- The menu service starts and loads a cache containing information about available dishes.

- This cache is distributed, enabling it to be shared across different services.

Starting the Order Service:

- When the order service starts, it recognizes the cache used by the menu service.

- The system facilitates a handshake between the services, allowing them to join the same cluster and establish a connection.

- Both services now know about each other. The menu service’s cache includes the list of dishes, and the order service synchronizes with this cache.

Demonstrating Synchronization Link to heading

Here’s how the two services interact:

Placing an Order:

- Imagine you want to place an order for a dish called “Spicy Tuna Roll.”

- The order service adds this item directly from its cache without needing to query the menu service because it already has the dish details stored.

Adding a New Dish:

- You add a new dish called “Vegan Burger” to the menu.

- This new dish is added to the menu database and the cache.

- The order service’s cache is instantly updated with this new dish, thanks to real-time synchronization.

Handling Failures Link to heading

What happens if the menu service goes down?

Menu Service Failure:

- Even if the menu service crashes, the order service remains fully operational.

- The order service retains its cache and can continue to function, adding and retrieving items without disruption.

Recovering the Menu Service:

- When the menu service comes back online, it reconnects with the order service.

- The system ensures the menu service’s cache is updated with any changes made during its downtime.

- This seamless recovery process keeps both services synchronized and operational.

Cache as a Contract Link to heading

A cache can be viewed as a contract, similar to a RESTful call returning a JSON response. If the cache schema is changed, it affects the dependent services. This requires communication and coordination to avoid breaking these services. Changing the cache is akin to changing a RESTful call contract. It’s worthwhile to forego loose coupling. This is reasonable when services are developed by a single team with a narrow scope and need to closely cooperate.

Eventual Consistency Link to heading

With eventual consistency, the data may not always be up-to-date. This trade-off must be accepted as part of using this approach. It takes time for information to propagate from the menu service to the order service.

Data Volume and Limited Scalability Link to heading

Consider a large cache of dish descriptions. The order service has all the descriptions, and querying the cache is fast. However, as more instances are created for scaling, the total memory size increases, potentially exceeding memory limits. This highlights the need for careful attention to cache size and scalability limits.

Loading entire dish descriptions into the cache may lead to inefficiencies. If a description for a specific dish is needed and it’s not in the cache, the service must be called, negating the benefits. Therefore, data volume is a significant consideration.

Additionally, a newly created menu service instance’s cache needs to be preloaded before becoming operational.