When we transition to microservices, each service owns its data. Achieving transactions across multiple services isn’t as straightforward as with a single monolithic database.

One way to address this challenge is through sagas, which simulate distributed transactions using a series of local transactions. This approach was popularized by Chris Richardson and later analyzed by Mark Richards and Neal Ford in their book ‘Sotware Architecture: The Hard Parts’.

They examined how these factors affect saga characteristics:

Communication style: synchronous vs asynchronous

Atomicity vs eventual consistency

Coordination: orchestration vs choreography

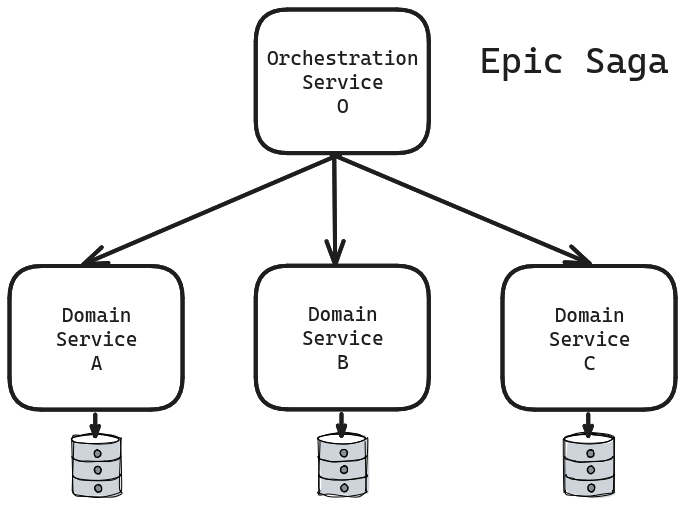

Mark and Neals identified eight possible configurations, each with its own trade-offs. The first configuration they named ‘Epic Saga’. The Epic Saga uses synchronous communication, orchestration, and atomicity.

Atomicity implies that the orchestrator either successfully completes all external calls on the first attempt, or if it fails midway, it cannot return until it compensates for all previously executed local service transactions. This constraint makes the Epic Saga highly dependent on the availability of individual services participating in the orchestration.

Let’s do a quick calculation. Assuming the availability of the orchestration service (‘alpha’) and the orchestrated service is also ‘alpha’, the probability of a synchronous request succeeding is ‘alpha^2’. If there are N orchestrated services, the total availability becomes ‘alpha^(2N)’. This multiplicative behavior arises due to the synchronicity constraint.

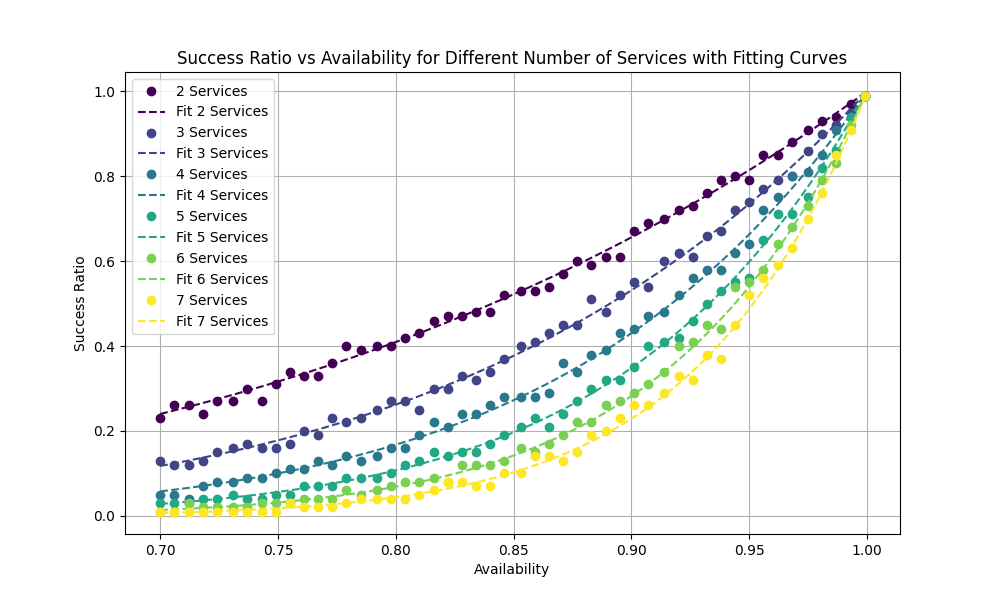

This means the success rate is exponentially sensitive to the number of services participating in the orchestration and their availability. Unless the services have high availability and are few in number, the saga may fail frequently wasting resources on compensation for failure limiting scalability.

We can observe this in computer simulations of orchestrated sets of services:

Here the success ratio is percentage of time the saga completes successfully with no compensation request. The simulation takes into consideration that the compensation request could also fail. We can see the fit matches exactly with formula derived above.

Distributed systems can be viewed as probabilistic systems where all scenarios can occur. I often struggle when someone explains why a particular failure scenario might occur in a system but doesn’t quantify the probability of it happening. I believe we must accept the nature of distributed systems and optimize for minimizing the probability of failure cases.

I will explore the seven remaining configurations in subsequent posts, aiming to quantify our metrics in each case. Sometimes my math skills might not suffice, and I’ll use computer simulations to gain insights into what’s happening. The ultimate goal is we can simulate hybrid sagas not only the discrete 8 configurations or even ask the computer to ‘inverse design’ the optimal saga.